In what I assume is a testament to my penchant for skepticism and in some cases, outright cynicism, I've received quite a bit of e-mail recently asking what I'm most "worried about" going into 2018.

First of all, the easy answer to that is simply this: "nothing that you're going to care about." On that, humor me for a (very) brief tangent.

The "worry" question gets posed every year to anyone who comments on markets with any regularity. When the question comes from individual readers or clients (as opposed to from media outlets that are looking to publish year-ahead pieces), it's almost always presented in a way that suggests the person doing the asking assumes that something market-related is going to be on the top of the commentator's "worries" list. That's an absurd assumption. That is, if what you really want to know is "what I'm most worried about in 2018", I can promise you that nowhere in the top five is anything to do with markets. That doesn't mean I don't live and breathe markets to a degree that might very fairly be described as "unhealthy", it just means that if you were to get a hold of my top five worries list for the coming year, you'd find things like "devastating hurricane wipes out the Heisenberg beach bungalow" not "VaR shock dents multi-asset portfolios."

Incidentally, the devastating hurricane worry has very nearly been realized three times in the past two years.

Ok, moving past that tangent (i.e., assuming we're talking specifically about the market context), what I'm most concerned about headed into 2018 is retail investor psychology, and in the same vein, I'm worried about what the ramifications of a bungled exit from central bank stimulus will be for well-meaning popular pundits. Regular readers will recognize this theme as it pervades a lot of what I write.

The difference between me and the people I'm often compared to is that I've actually been in some dicey situations in my time and without elaborating, suffice to say I can spot malice a mile away. So very much unlike a lot of market skeptics and so-called "permabears", I do not think that central bankers have a nefarious master plan and I do not think that the popular pundits you might follow on Twitter or see everyday on CNBC are trying to deceive you.

Rather, what's happened over the last nine or so years is that policymakers have been forced into a situation where they cannot publicly acknowledge the extent to which ZIRP, NIRP and QE have inflated bubbles in financial assets because doing so might well destabilize markets. That's not "dishonest." It's just common sense. You're not going to deliberately do something that could trigger a meltdown.

Obviously, the Fed, the ECB, and the BoJ are acutely aware that flooding the market with $15 trillion in liquidity via massive purchases of government bonds, corporate bonds, and equities has driven up asset prices. After all, they explicitly set out to create a hunt for yield (just ask Ben Bernanke). These asset purchases by definition distort supply/demand by engineering a shortage of purchasable assets (supply) and compressing risk premia (demand, as that creates voracious appetite for anything with a positive yield). What happened here is that they assumed the transmission mechanism from monetary policy to the real economy was more efficient than it actually is. In other words, it has taken a lot longer than they anticipated to create a synchronized upturn in global growth and they still aren't there on the inflation targets.

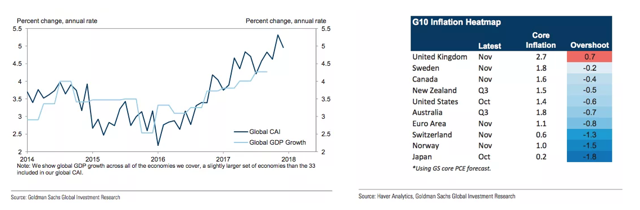

(Goldman)

See what I mean? We're just now (i.e., after eight years of stimulus) seeing a synchronized global recovery (left pane) and we're still well short of the inflation targets across DM economies (right pane).

They were pot-committed to seeing this through a long time ago, so they effectively had to persist until they "won" at least one battle (i.e., either growth or inflation). All the while, stimulus continued to inflate financial assets. The proliferation of low-cost ETFs supercharged the dynamic by giving retail investors easy access to every corner of the market be it something as simple as the S&P (SPY) or something that was previously esoteric for mom and pop like junk bonds (HYG). Those flows were encouraged as asset prices continued to rise on the back of stimulus and thus the "wave paradox" was born. Investors are no longer sure whether the decisions they're making are good or whether the decisions they're making only turned out good by virtue of their having made them.

Popular pundits have gotten swept up in this. They don't understand it. Which is a tragedy because in many cases they have access to the research they would need to get a handle on it.

Let me give you two actual, real-life examples from Twitter exchanges I've had with two widely-followed names this month. I'm going to remove the names here because the point is certainly not to malign anyone, rather the point is to reinforce the idea that the people the public relies on the covey financial wisdom don't grasp the dynamic.

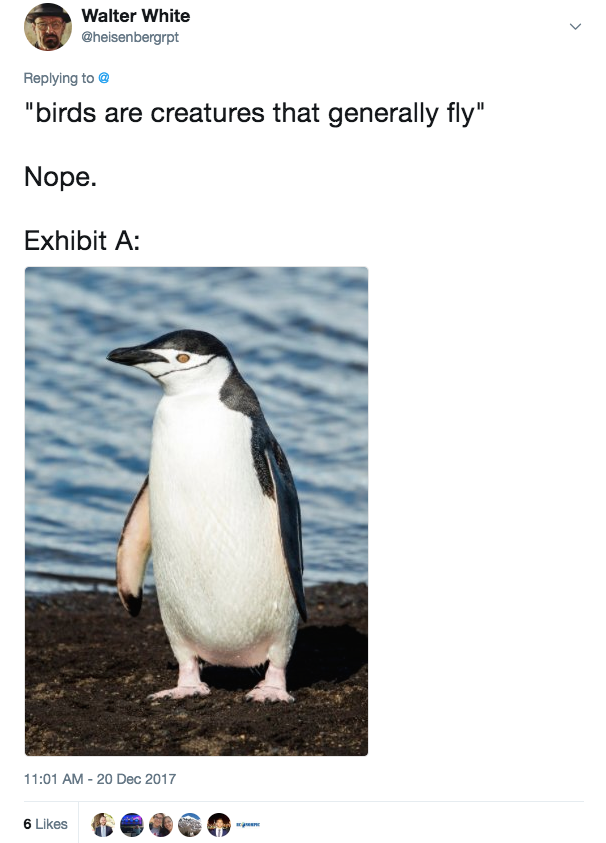

Ok, here's the first one:

So that's a chart of the Dow and a chart of General Electric (NYSE:GE), and as you can see, the contention there is that because the Dow is up and GE is down over an arbitrary time frame, indiscriminate flows from passive investing are not supercharging the market rally.

For one thing, the tweet there makes no sense. This (very popular) personality is essentially saying that indiscriminate flows are not indiscriminate. Indexing is indiscriminate. There's no question about it. Even if you want to split hairs, there is no world in which indexing is not at least in some sense indiscriminate. What does indexing even mean if there's not an indiscriminate element to it?

But beyond that, the logical fallacy there is so blatant that I had a hard time figuring out how to communicate the inherent absurdity. Of course, it's me we're talking about, so you can bet your bottom dollar I found a way. To wit:

Again, the problem here is that this person has something like 950,000 Twitter followers who depend on him for accurate information and there is absolutely nothing accurate about what's implied in the first tweet shown above. And it's not harmless. Far from it. It serves to make retail investors think that there's no merit to the idea that indexing, by virtue of its indiscriminate character, is creating distortions. It unquestionably is. Just ask Howard Marks or Goldmanor Arik Ahitov and Dennis Bryan or Wells Fargo or any of the other countless examples I'll be happy to send you if you care to e-mail me.

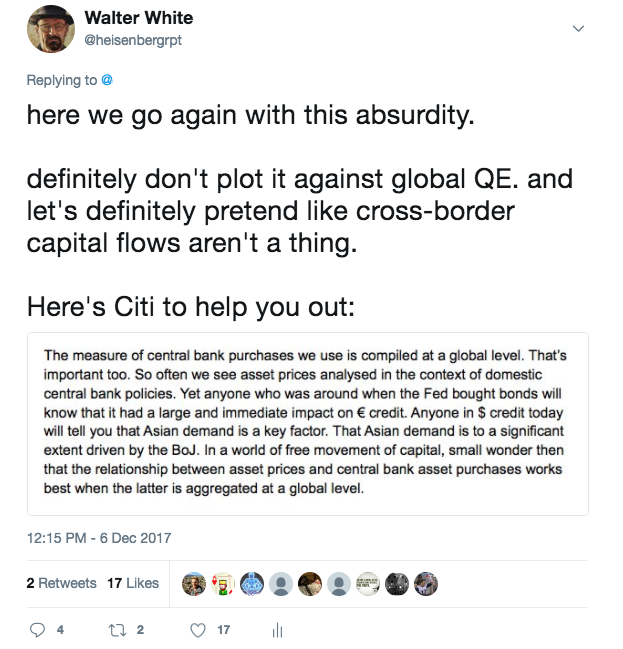

Let's move on to the second example. Here's the initial tweet (and this is from a different popular pundit):

And here is my initial response:

That kicked off a lengthy exchange between the pundit and followers. I didn't participate much further, but I did offer the following chart which plots rolling central bank asset purchases against HY spreads:

Unfortunately, the pundit in question decided to respond as follows:

Got that? Citi deliberately started the chart in 2010 "because it would totally break down before that."

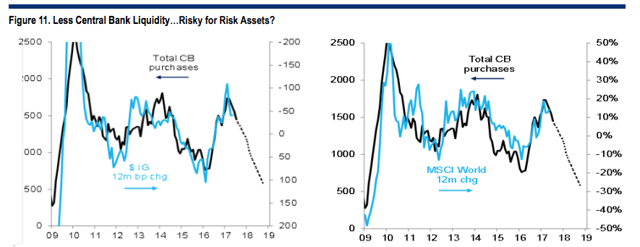

Because I am actually a much nicer person than I'm given credit for, I didn't have the heart to show him the following two charts which, while slightly different (they plot 12-month rolling change in global central bank liquidity versus IG credit and global equities), completely refute that commentator's "chart crime" contention:

(Citi)

As you can see, those charts start in 2009. There is no "chart crime." There is just a popular pundit who doesn't seem to grasp what's going on and the truly strange thing about the contention that it's a "chart crime" to plot global central bank purchases against spreads starting in 2010 is that the global plunge into QE started in 2009, so I'm not sure what this person expects. That is, if what we're talking about is post crisis monetary policy's effect on global assets, what kind of sense would it make to use charts that date to before those policies were implemented?

Those are two rather poignant examples that illustrate why I'm worried about retail investor psychology and about what the ramifications of a bungled exit from central bank stimulus will be for well-meaning popular pundits.

When it becomes apparent (and it will) that this tsunami of liquidity and constant policymaker communication with markets were together the proximate cause of the rally in global financial assets, there is going to be a crisis of confidence among retail investors. They're going to lose confidence in themselves because they will realize that a decade's worth of gains were engineered, they're going to lose confidence in popular pundits who have taken it upon themselves to keep the investing public informed, and perhaps most importantly, they're going to lose confidence in policymakers if those policymakers do not manage to pull off an orderly exit from the post-crisis policy regime.

One reason this is particularly concerning to me is that losing confidence in oneself and in well-meaning pundits and policymakers is something completely different from being angry at a group of people you already suspected of being inherently shady in the first place. After 2008, the blame was placed squarely on the shoulders of Wall Street, and while that shook confidence in the nation's financial system, Main Street distrusting Wall Street was hardly a new phenomenon.

To be sure, investors profess to be skeptical of the punditry. But look how many likes and retweets the chart of the Fed balance sheet and the S&P shown above received. That represents (at least in part) trust in the personality who tweeted that highly dubious graph. Do note that the reason it's dubious has everything to do with the caption. That is, the chart is just the chart. It's the caption that's misleading. In the same vein, the personality that tweeted the GE/Dow chart is the single-most followed pundit on FinTwit (for those who aren't up on the lingo, "FinTwit" is just shorthand for the finance Twitter "community"). So feigned skepticism of the punditry aside, these folks are widely respected as something akin to authorities on these matters. Obviously, there are countless examples of people who fall into the same category.

Finally, one could argue that distrust in policymakers is not only not new, but is in fact endemic in America. That would be true of politicians. And as much as you and I (i.e., people who enjoy talking about markets) might have reservations about the collective wisdom of central bankers, the vast majority of the stock-holding public couldn't tell you the first thing about the Fed and I think it's entirely reasonable to suggest that most people who have a 401k wouldn't be able to tell you what the acronyms "ECB" and/or "BoJ" even stand for. Now imagine trying to communicate to those people how a few missteps on the way to exiting something called "quantitative easing" ended up accidentally sinking their passive portfolio. If you thought people were confused about how CDOs and MBS tanked the market in 2008, just wait until someone tries to explain to them how QE works.

Let's leave aside the obvious near to medium term implications for markets (e.g., panic selling when everyone scrambles to figure out how an errant bit of overly aggressive forward guidance triggered a rates tantrum that spilled over into equities and, further, why that should even matter if QE wasn't behind the rally as all the pundits claimed). The bigger question is what kind of longer-term psychological impact this will have on retail investors and on pundits who I firmly believe are well-meaning and who are in fact far more concerned about your financial well-being than Heisenberg, with the only issue being they don't seem to know what they're talking about.

We do not need another mass crisis of confidence triggered by the unwind of the very policies that were instituted to calm everyone down after the previous crisis of confidence.

Coming full circle, how truly "worried" about this is Heisenberg? Well, in the grand scheme of things, not very. America's capital markets are deep and highly liquid (liquidity problems stem not so much from the markets themselves, but from policy and from "innovations" that have altered market structure). Additionally, it seems unlikely that policymakers wouldn't step in to ensure that the bottom doesn't fall out as a result of their inability to rollback stimulus. That's the spiraling bubble dynamic whereby the policy response to each burst bubble must be large enough to create a new bubble big enough to subsume the last one. Theoretically, that can go on in perpetuity. Lastly, I have a lot of faith in the resiliency of the system in general and I do not believe that there is any chance that creative destruction will ever be allowed to take hold - central banks will literally send everyone checks in the mail before they let the soup lines start forming.

But what does concern me slightly (and I'm a selfish guy, so I do mean "slightly") is the prospect that I'll be proven right. Contrary to popular belief, I have absolutely no desire to see retail investors experience the mental shock that would come with discovering that a series of policies which the masses have been assured aren't the sole source of market gains are in fact the proximate cause for those gains. I'd much rather see central banks stick the proverbial dismount from the policy balance beam so that no one is the wiser.

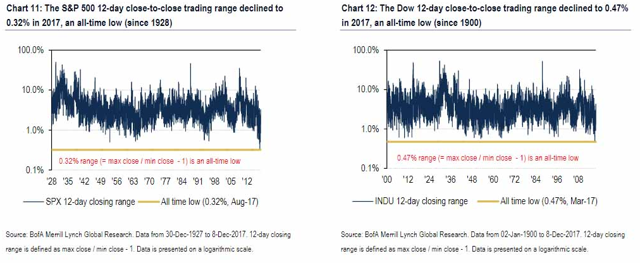

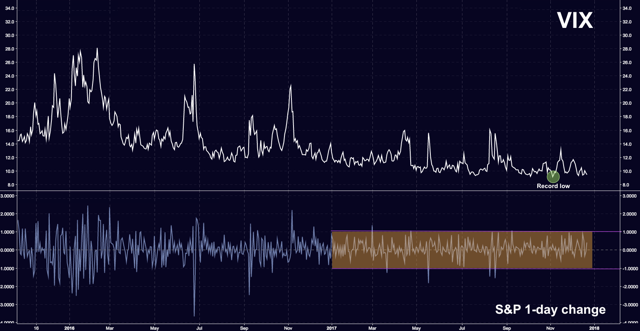

In the meantime, do note that the historical anomalies are adding up. As BofAML recently pointed out, US equity trading ranges hit 110-year lows in 2017:

(BofAML)

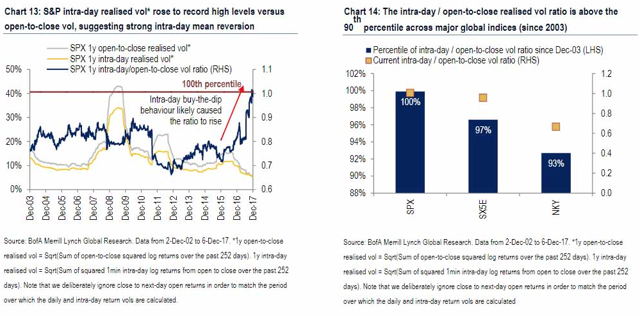

And the buy-the-dip mentality is manifesting itself in all sorts of ways (take a second to read the captions on the following charts - they are self-explanatory):

(BofAML)

Overall, this is what the landscape looks like from a 30,000-foot perspective:

One way or another, that has to break.

There's my 2018 outlook. Hopefully, it lived up to your expectations, whether they were high or low.

Disclosure: I/we have no positions in any stocks mentioned, and no plans to initiate any positions within the next 72 hours.

I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.